What the Three Mile Island and Modern Cyber Incidents Have in Common

Rick Lemieux – Co-Founder and Chief Product Officer of the DVMS Institute

Introduction: Different Domains, Shared Lessons

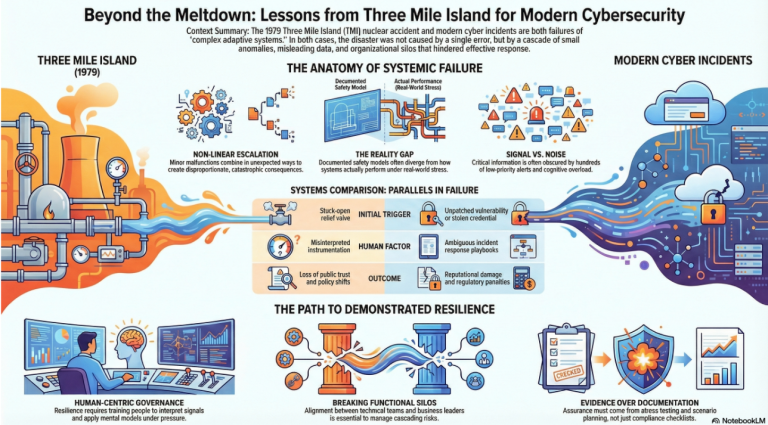

At first glance, the 1979 Three Mile Island (TMI) nuclear accident and modern cybersecurity incidents appear to belong to entirely different domains. One involved a partial nuclear reactor meltdown in Pennsylvania; the other typically involves malicious code, stolen data, or disrupted digital services. Yet beneath the surface, both reflect systemic failures in complex, tightly coupled socio-technical systems. Each reveals how technology, human decision-making, organizational design, and governance interact under stress. When examined through the lens of resilience and assurance, Three Mile Island and major cybersecurity incidents share striking commonalities that offer enduring lessons for digital enterprises.

Complex Systems That Fail in Non-Linear Ways

Both nuclear power plants and modern digital enterprises are complex adaptive systems. They contain thousands of interdependent components, automated safeguards, human operators, and feedback loops. In such systems, failure rarely results from a single catastrophic mistake. Instead, it emerges from a chain of small, interacting anomalies that escalate in unexpected ways.

At Three Mile Island, a relatively minor mechanical malfunction, a stuck-open relief valve, combined with misleading instrumentation and operator assumptions to create a cascading crisis. In cybersecurity incidents, an unpatched vulnerability, a misconfigured identity role, or a compromised vendor credential can similarly combine with routine operational activity to produce disproportionate consequences. In both cases, the system does not fail because no controls existed; it fails because controls interact in ways designers did not fully anticipate. Complexity amplifies small deviations into systemic risk.

The Gap Between Design and Reality

A defining feature of the Three Mile Island incident was the divergence between the plant’s designed safety model and the reality operators faced in the control room. Instrumentation did not clearly indicate that coolant was escaping. Operators misinterpreted signals because their training emphasized certain failure scenarios over others. The “paper system” of engineered safeguards did not align with the “living system” of human interpretation under pressure.

Cybersecurity incidents exhibit the same gap. Organizations maintain policies, diagrams, and control frameworks that describe how systems should behave. Access controls are documented. Monitoring processes are defined. Incident response playbooks are approved. Yet during an actual breach, teams often discover that logging was incomplete, alert thresholds were poorly tuned, or escalation paths were ambiguous. The documented architecture differs from the operational reality. In both nuclear and digital contexts, resilience depends not merely on design, but on how the system performs under real-world stress.

Misleading Signals and Information Overload

At Three Mile Island, operators were overwhelmed by alarms—hundreds of alerts triggered in a short period. The sheer volume of signals obscured the root cause. Critical information was technically available but not cognitively accessible in a way that supported rapid understanding.

Modern cybersecurity operations centers (SOCs) face a similar challenge. During a major incident, analysts may confront thousands of alerts, many of which are false positives or low-priority events. Signal competes with noise. Teams struggle to distinguish early indicators of systemic compromise from routine anomalies. Attackers exploit this reality by blending malicious activity into normal traffic patterns.

In both scenarios, the problem is not the absence of data but the lack of clarity. Systems generate information without ensuring it supports sound decision-making under pressure. When cognitive overload replaces situational awareness, small errors compound.

Human Factors Under Stress

Three Mile Island underscored the centrality of human factors in high-risk environments. Operators made decisions consistent with their training and understanding, yet those decisions inadvertently worsened the situation. Under uncertainty, they acted to preserve what they believed was reactor integrity, unaware that coolant levels were dangerously low.

Cybersecurity incidents similarly unfold in high-pressure environments where time, ambiguity, and incomplete information shape behavior. Incident commanders must decide whether to isolate systems, shut down production, notify regulators, or negotiate with attackers. Misjudgments are rarely due to incompetence; they arise from the difficulty of interpreting evolving conditions within complex systems.

Both cases demonstrate that resilience cannot rely solely on technical controls. It must account for how people interpret signals, apply mental models, and coordinate action under stress. Training, rehearsal, and clear decision rights are as critical as engineered safeguards.

Organizational Silos and Communication Breakdowns

Another parallel lies in organizational structure. Investigations of Three Mile Island revealed communication gaps between engineering teams, management, regulators, and plant operators. Information was not always shared or contextualized effectively. Decision-making authority and situational understanding were unevenly distributed.

In cybersecurity incidents, similar silos frequently emerge. Security teams detect anomalies but struggle to gain attention from business leaders. IT operations may resist system shutdowns due to service commitments. Legal, compliance, and communications teams become involved only after escalation. Fragmented governance slows coordinated response.

When roles, responsibilities, and escalation paths are unclear, the system’s ability to contain failure weakens. Both nuclear and digital incidents reveal that resilience is not just technical; it is organizational. Alignment across functions is essential to manage cascading risk.

The Illusion of Safety

Prior to Three Mile Island, the nuclear industry possessed strong confidence in its safety systems. Plants were engineered with multiple redundant safeguards. Regulatory frameworks were established. The accident exposed how confidence based on design assumptions can mask untested vulnerabilities.

Similarly, many organizations enter cybersecurity incidents with high confidence, based on compliance certifications, audit reports, and risk dashboards. Controls appear mature. Policies are up to date. External assessments yield favorable ratings. Yet a single successful phishing campaign or software supply chain attack can reveal systemic blind spots.

In both contexts, reassurance—confidence derived from documentation—proved insufficient. Assurance requires evidence that systems can withstand real-world stress, not just that safeguards exist in theory.

Cascading Consequences Beyond the Immediate Event

The impact of Three Mile Island extended far beyond the reactor itself. Public trust in nuclear energy declined sharply. Regulatory scrutiny intensified. Industry economics shifted. The incident reshaped policy and perception for decades.

Cybersecurity incidents have comparable ripple effects. A breach can erode customer trust, depress stock value, trigger regulatory penalties, and invite class-action lawsuits. Supply chain disruptions can affect downstream partners and customers. Reputational damage often exceeds direct technical loss.

Both events illustrate that in interconnected systems, localized failures produce systemic consequences. The true cost of disruption includes intangible factors such as trust, legitimacy, and strategic momentum.

Regulatory and Governance Evolution

In the aftermath of Three Mile Island, the nuclear industry underwent significant reform. Operator training improved. Control room designs were re-evaluated. Regulatory oversight intensified. The event catalyzed a shift toward a more rigorous safety culture and performance monitoring.

Cybersecurity regulation is following a similar trajectory. Major breaches have prompted expanded disclosure requirements, stricter data protection laws, and increased board-level accountability. Regulators now expect evidence of resilience, not just compliance with baseline controls.

Both domains demonstrate how high-impact incidents drive governance evolution. Crises reveal systemic weaknesses that routine oversight fails to detect. The challenge for modern enterprises is to learn proactively rather than reactively.

The Central Lesson: Resilience Must Be Demonstrated

Perhaps the most enduring commonality between Three Mile Island and cybersecurity incidents is this: resilience must be demonstrated, not assumed. Safety mechanisms at TMI were real, yet they were not sufficient under the specific conditions that emerged. Cybersecurity controls are often real, yet they may not perform as expected when adversaries exploit unanticipated interactions.

Demonstrated resilience requires stress testing, scenario planning, and continuous learning. It demands that organizations examine how systems behave when degraded, not only when functioning normally. It requires bridging the gap between documentation and lived reality.

Conclusion: Governing Living Systems

Three Mile Island and modern cybersecurity incidents remind us that high-risk systems fail at the intersection of technology, people, and governance. Both reveal the danger of mistaking procedural completeness for operational readiness. Both show how complexity, cognitive overload, and fragmented accountability can transform manageable anomalies into systemic crises.

The lesson for digital enterprises is clear. Cyber resilience cannot be confined to technical safeguards or compliance artifacts. It must be governed as a living capability—continuously monitored, tested, and improved. Just as the nuclear industry was forced to confront the realities of complex system failure, today’s organizations must recognize that cybersecurity incidents are not merely technical events. They are manifestations of systemic fragility. And, like Three Mile Island, they offer a choice: respond with incremental documentation or fundamentally strengthen the system’s resilience.

About the Author

Rick Lemieux

Co-Founder and Chief Product Officer of the DVMS Institute

Rick has 40+ years of passion and experience creating solutions to give organizations a competitive edge in their service markets. In 2015, Rick was identified as one of the top five IT Entrepreneurs in the State of Rhode Island by the TECH 10 awards for developing innovative training and mentoring solutions for boards, senior executives, and operational stakeholders.

Digital Value Management System® is a registered trademark of the DVMS Institute LLC.

® DVMS Institute 2026 All Rights Reserved